Indonesia’s coral reefs, among the most biodiverse marine ecosystems in the world, are under increasing pressure. According to 2019 data from LIPI, only around 6% of Indonesia’s reefs remain in excellent condition, while 35% are considered in poor health. Threats come from all directions: pollution, destructive fishing practices, climate change, coastal reclamation, and ship groundings.

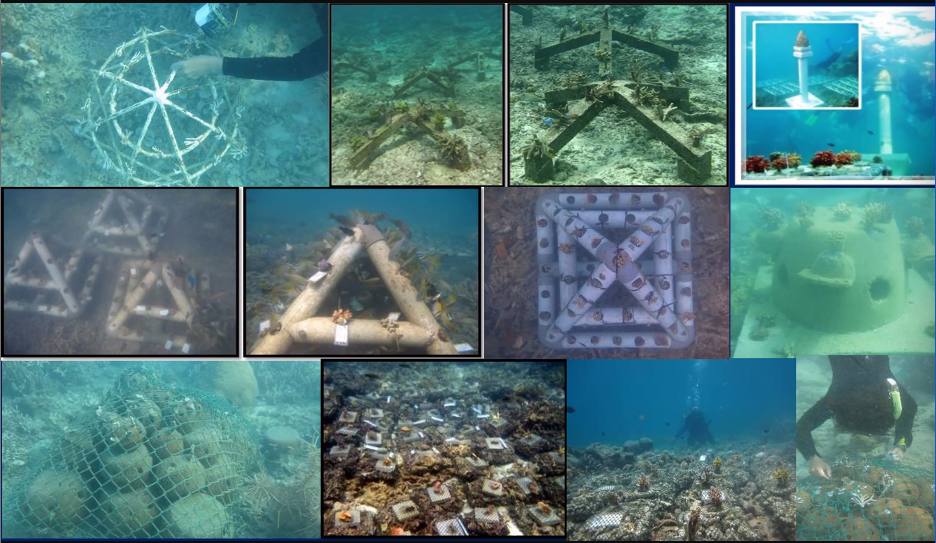

Amid these challenges, the Indonesian Coral Reef Foundation (TERANGI) has taken an active role in marine ecosystem recovery through coral reef restoration projects in the Seribu Islands and Banten. As shared by Idris, a representative from TERANGI, reef restoration is not just about planting coral—it’s about ongoing care, consistent monitoring, and strong community involvement.

Restoration Is More Than Just Planting

In his presentation, Idris emphasized the importance of distinguishing between restoration and rehabilitation. Restoration aims to return an ecosystem to its original state, while rehabilitation focuses on recovering the ecosystem’s function, even if the coral species used are different, as long as they provide similar ecological roles.

TERANGI implements a three-phase approach: pre-activity, implementation, and post-activity. The post-activity phase includes monitoring and maintenance, which are key to the long-term success of any restoration effort. Success, Idris notes, is not determined by the planting process alone, but especially by what happens afterward.

Maintenance is carried out in three stages. The initial phase involves clearing threats to coral health, such as the crown-of-thorns starfish (Acanthaster planci) and predatory snails like Drupella and Coralliophila, which can be found on both natural and artificial reefs. Over time, the frequency of cleaning decreases, but monitoring continues for 2–3 years after installation.

Field Data: From Coral Growth to Fish Behavior

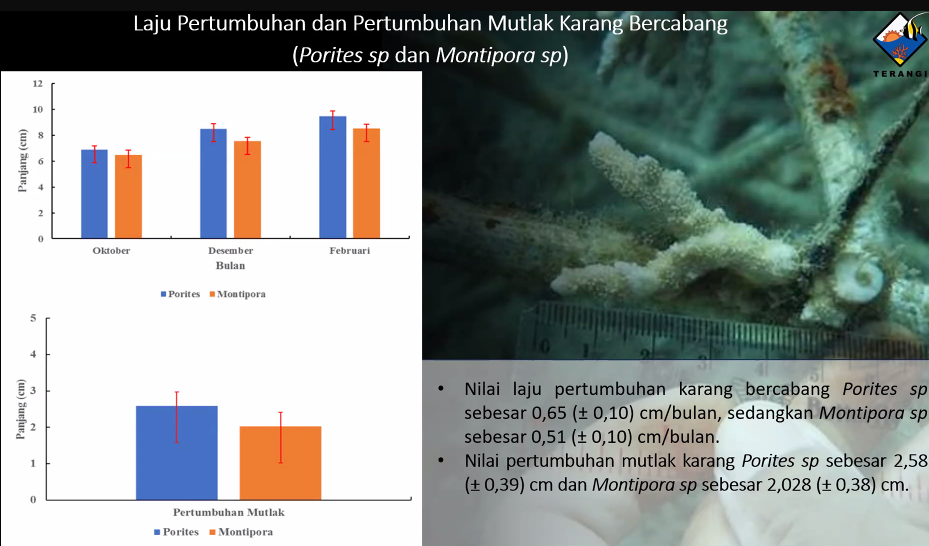

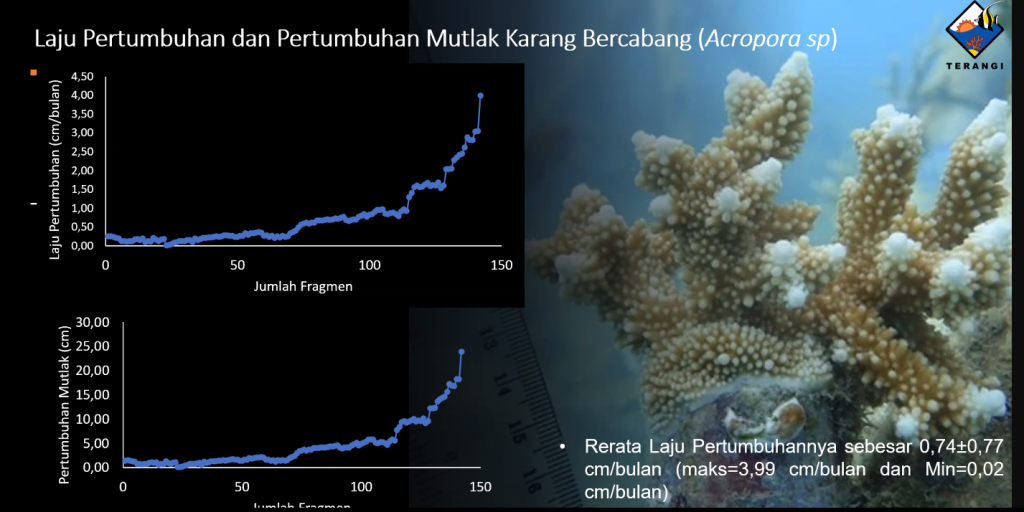

During the monitoring phase, TERANGI’s team collects data on coral growth across various species. For example, Acropora sp. exhibits an average growth rate of 0.74 cm/month, with a 64% survival rate after completing all three care phases. Meanwhile, massive corals such as Platygira sp. and Favites sp. grow more slowly but are more resistant to environmental stress.

Data also show a correlation between the initial fragment size and coral growth. Coral fragments between 11–20 cm demonstrate the best growth, especially among branching corals. For massive coral types, more research is needed to determine the ideal fragment size.

Monitoring also includes associated biota, such as reef fish and non-coral benthic organisms. Interestingly, fish populations were found to be higher on artificial reefs than on natural ones. However, in terms of behavior, fish were more likely to reside on natural reefs (52%) than artificial ones (only 37.5% stayed, while the rest were transient or foraging).

Recommendations: Not Just Rehabilitation, But an Ecosystem-Based Approach

Idris stressed that restoration efforts should be grounded in a holistic ecosystem approach. TERANGI’s key recommendations include:

- Restoration areas should match the extent of the damaged zone.

- Transplanted coral species should represent the natural lifeforms found at the site.

- Coral cover from restoration should approach the natural reference site’s cover.

- Behavior and presence of associated biota (e.g., fish, benthic organisms, coral recruits) are vital indicators of restored ecosystem function.

Local community involvement must be central to maintenance and stewardship.

Communities as Frontline Guardians

In the Seribu Islands, TERANGI has developed a community-based monitoring network involving tourism operators, fishers, and local residents in coral reef maintenance and observation. This initiative is not just about conservation—it’s about fostering a sense of ownership and responsibility for the ocean, which remains the foundation of their livelihoods.

“Ecosystem recovery is not just a scientific task,” Idris concluded. “It’s a collective effort—between scientists, communities, and nature itself.”