North Bali, Indonesia – In the quiet coastal waters of North Bali, an ambitious reef restoration effort is underway, driven by a combination of science, community empowerment, and citizen participation. Led by Dr. Zach Boakes, co-founder of the North Bali Reef Conservation (NBRC) and postdoctoral fellow at Indonesia’s National Research and Innovation Agency (BRIN), this initiative is showing signs that artificial reefs can help revive degraded marine ecosystems and the communities that rely on them.

Over the past seven years of experimentation and adaptation, the results are promising: signs of ecological recovery are emerging, and the project is offering hope for coral reef restoration efforts worldwide.

While artificial reefs cannot replace nature, they can serve as stepping stones for recovery. “Ultimately, we’re trying to restore some of the lost ecosystem services, biodiversity, fisheries, even carbon storage,” Dr. Boakes says. “And in doing so, we’re restoring hope for communities that depend on the sea.”

Bali Reefs Under Threat

Bali’s coral reefs, especially along the northern coast, have suffered years of degradation. Dr. Boakes highlights three major threats: physical damage, plastic pollution, and coral bleaching. Historically, coral mining for construction destroyed large areas of the reef. Although now illegal, the damage to the ecosystem persists. Anchoring, destructive fishing, and careless tourism continue to inflict harm.

Plastic pollution, particularly during the monsoon season. Additionally, coral bleaching has led to corals expelling their symbiotic algae due to rising sea temperatures, posing a significant existential threat. “Climate change has already wiped out around 50% of coral reefs globally,” Dr. Boakes says.

Founded in 2017, North Bali Reef Conservation began as a conservation effort that works closely with local fishing communities. The team identified degraded reef areas and began installing artificial reef structures, blocks made from a mixture of sand, cement, and calcium to provide a foundation for coral to grow.

To date, over 30,000 artificial reef units have been deployed. “We started in areas with almost no coral or fish,” Dr. Boakes explains. “Now, after just three years, we’re seeing significant coral growth and fish recruitment.”

Coral Restoration Monitoring Makes the Difference

Indonesia has one of the highest numbers of reef restoration programs in the world, yet monitoring remains one of the weakest activities. “It’s expensive and time-consuming, so it’s often skipped,” says Boakes. But skipping monitoring can mean missing vital information about what works—and what doesn’t.

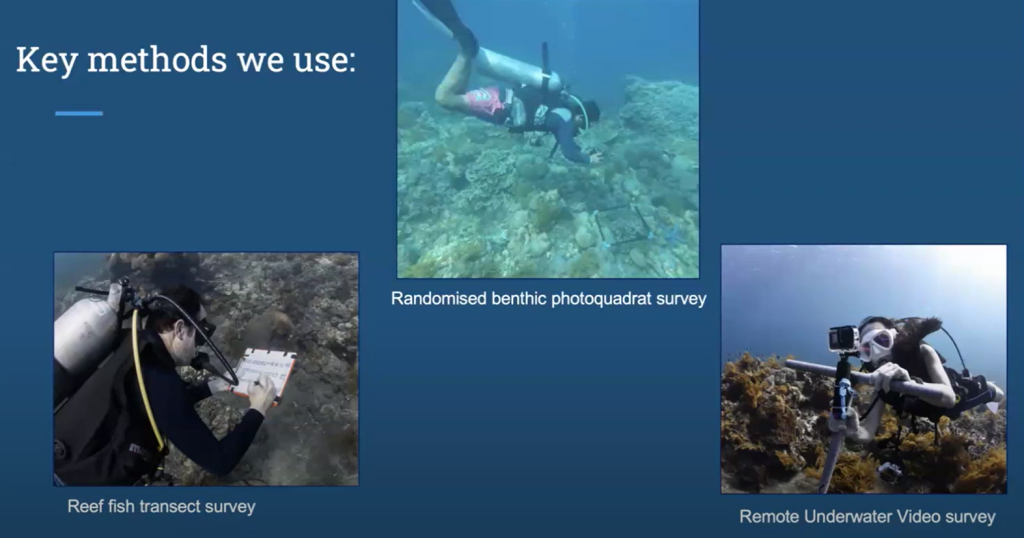

In North Bali, continuous monitoring has allowed the team to refine their reef designs, shifting to more effective structures based on ecological data. These include fish transect surveys, benthic quadrat sampling, and the use of Remote Underwater Video (RUV).

After three years of monitoring, data suggests that artificial reefs are beginning to function like natural ones. Fish biodiversity and abundance have increased, and nutrient cycling (phosphates and nitrates) shows signs of similarity to natural systems. “They’re even starting to store carbon in comparable ways,” Boakes notes.

Still, artificial reefs are not a perfect substitute. “It might take a decade or more for them to replicate the ecological functions of a mature natural reef fully,” he adds.

Monitoring isn’t just about data — it’s about sharing that data. Dr. Boakes encourages restoration projects to go beyond internal reporting. “Publishing in scientific journals helps integrate your findings into the global conversation on reef science,” he says.

He advises setting clear hypotheses, choosing methods aligned with the research questions, and considering the broader “so-what”-how the data contributes to addressing global reef challenges.