Restoration isn’t just about putting corals back in the ocean,” Leon explains. “The real work starts after the planting, when we maintain, monitor, and adapt

In the clear waters off Padangbai, Bali, a quiet but powerful coral reef restoration effort is showing how consistency, community, and long-term care can bring degraded reefs back to life. For Leon Bay, founder of Livingseas, coral restoration is only the beginning of a much longer journey.

Fromm Rubble to Reef

Since 2019, Livingseas has been working to restore a massive 50,000 square meters of coral reef in the Padangbai area. The site, once devastated by blast fishing and anchor damage, was left covered in rubble. “The reef was gone,” Leon says. “It was just broken substrate, unstable, and unable to support new coral life.”

Their solution involved a mix of reef structures, from reef stars to their innovation: Super Stars, larger frames designed to elevate coral off unstable seabeds and avoid smothering by sediment.

In time, the team discovered that reef restoration is not just a matter of engineering, but also ecological observation. A creative experiment, placing concrete-based bottles between structures, resulted in corals like Galaxea covering them after four years. These trial-and-error methods, Leon notes, are part of understanding how different coral species respond.

Maintenance and Monitoring is the Key

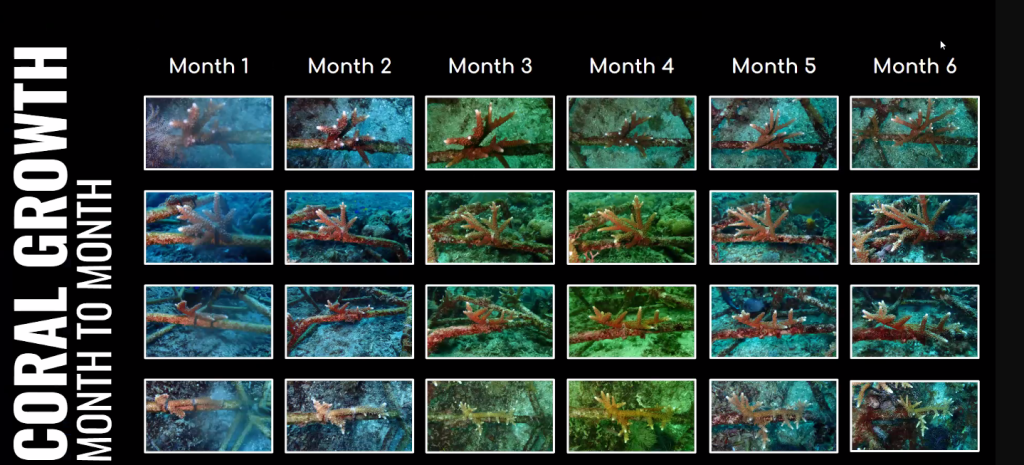

While some projects focus solely on installing structures, Livingseas emphasises ongoing maintenance, especially in the crucial first 1–6 months after coral planting.

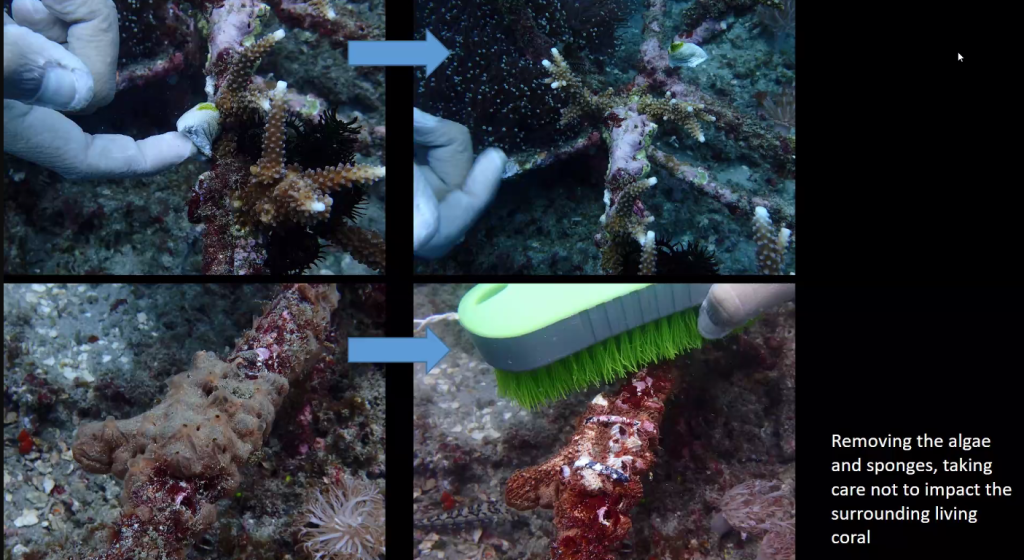

“Without regular cleaning, algae takes over,” says Leon. “That’s why so many large-scale projects fail. The structures are there, but they’re covered in algae instead of coral.”

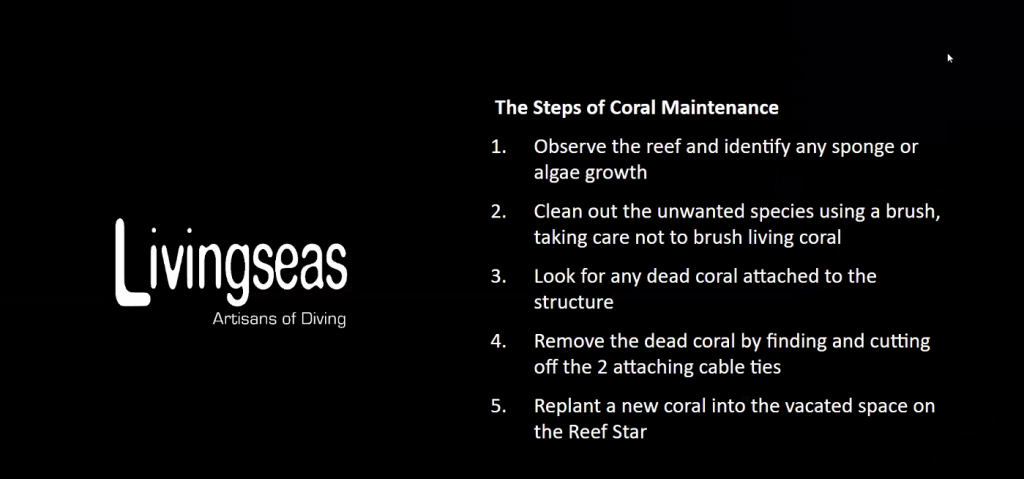

Maintenance activities include: 1.) Removing algae, dead coral, and sponges, 2.) Replacing dead fragments, 3.) Ensuring corals grow over cable ties and into the structure

Leon notes that after six months, coral growth stabilises, and maintenance becomes less frequent. But neglecting this early phase can undo all previous efforts.

Every six months, Livingseas conducts scientific monitoring of coral cover and fish abundance. But monitoring, Leon insists, doesn’t always require high-tech tools. “Sometimes we just swim around to see what’s working, what’s dying, or what’s growing too fast.”

These informal checks are often just as necessary, helping the team understand ecosystem changes in real-time. Observations from monitoring have even led to the development of underwater nurseries, holding spaces for leftover coral fragments that would otherwise die.

Their approach is flexible yet data-informed. Coral tables, rope structures, and varied coral morphologies are used based on the site’s needs. For Leon, diversity is the goal, not just of coral species, but of habitat functions.

Perhaps the most compelling sign of success? The return of life once lost. In recent years, reef sharks, sea turtles, and even the elusive Napoleon wrasse (Cheilinus undulatus) have been spotted near the restored reefs of Padangbai.

“When top predators return, that tells us the ecosystem is functioning again,” Leon says.

The story of Livingseas offers a simple but powerful message: restoration without monitoring and maintenance is not restoration at all. True success lies not just in planting coral, but in sticking around to make sure it thrives.

As Leon puts it, “We’re not just building reefs—we’re rebuilding futures, one coral at a time.”